Why RNA Tech Transfer Is So Hard — And How the Field Can Fix It

By Victoria Fong, independent RNA consultant

Despite the visibility of COVID vaccines, most RNA products face a steep path to manufacturability. Here's why tech transfer — the bridge from innovation to GMP — is uniquely difficult for RNA.

RNA as a therapeutic modality has been swirling in academic circles for decades. However, only two mRNA therapeutics have been approved by the FDA for commercial use – Pfizer’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 products. Beyond these outliers, only a handful of non-mRNA therapeutics have reached the market, most with far narrower clinical visibility.

When the RNA pipeline is vast and preclinical and early clinical studies show extreme promise, it can be difficult to remember that not many RNA therapeutics have crossed the regulatory finish line. That does not mean RNA therapies are “behind.” Pharmaceutical development is inherently slow. But it is a reminder that RNA in the clinic is new and everyone in the field is still finding their feet – from R&D and CMC (chemistry, manufacturing, and controls) to clinical and regulatory.

Currently, mRNA and mRNA-LNPs are considered two separate products, each requiring release. There are few reliable CDMOs equipped with the knowledge and capacity for mRNA production, fewer still with strong LNP understanding, and almost zero with full end-to-end manufacturing and analytical testing. mRNA-LNP know-how is still limited to startups and other developing companies.

mRNA and LNPs also have quite different processing and analytical requirements. Since the drug substance (DS) and drug product (DP) often require discrete technologies, methods, and equipment, existing CDMOs have not committed to creating capacity for both. For small biotechs, coordinating two CDMOs is often more burdensome — not less. Further, most young biotechs with great technology and niche RNA-LNP knowledge have little CMC and manufacturing science and technology (MSAT) experience.

Failure of either party to scope out requirements and expectations early in the partnership can lead to disappointment. When selecting a CDMO that claims to manage both RNA and LNP, all stakeholders must be prepared for a hefty hands-on experience.

Trust and patience must be prioritized. The tech transfer requires extremely transparent communication and planning, rigorous gap analyses, risk assessments, and extensive training. For a young, inexperienced, and fast-paced biotech aching to get into the clinic, this may become a pain point.

Consistency Vs. Robustness

Developers usually know their process extremely well. They have made their product countless times in-house, achieving repeatable and reliable results. They present it to a CDMO and suddenly see issue after issue.

mRNA-LNP production is reproducible but highly tailored. Additionally, the processes are extremely sensitive to change. In both DS and DP manufacturing, the initial unit operation dictates downstream needs. It is the most critical, yet also the most variable and inconsistent when transferring between sites and personnel.

For mRNA, the complex in vitro transcription (IVT) reaction generates the target molecule along with impurities, and the quantity of both may vary depending on raw material quality and process control at this step.

For DP, the lipid and mRNA mixing step requires exceptionally specific conditions. Changing pumps or pump heads, tubing length, tubing diameters, or flow rates or a shift in N/P ratio can result in deviations to product critical quality attributes (CQAs) like LNP size, encapsulation, and polydispersity that must be understood.

mRNA-LNP manufacturing has not reached the robustness and flexibility that facilitate simple tech transfer. Like any emerging modality, what appears “optimized” at bench scale often becomes a liability at GMP scale — especially when tech transfer is delayed.

With LNPs specifically, the first mixing step has no universally standardized bioprocess technology. It is the least robust, scalable, and tech transfer friendly process in the whole production.

Leveraging a CDMO’s process development capability with entire teams experienced using various bioprocessing techniques with manufacturing in mind and multiple types of equipment available in their pilot labs could eliminate typical tech transfer headaches. Partnering with a CDMO early to streamline R&D to manufacturing may also blur process ownership, a decision requiring a detailed cost-benefit analysis.

Rapid And Ongoing Development

To improve robustness and address manufacturing concerns, the field is rapidly advancing the technology for design, materials, and production of the DS and DP, while expanding on potential therapeutic areas.

mRNAs are large molecules, and the scalability and performance of typical purification methods are currently good but not great. In a world where the ideal timeline of getting the drug to the patient is getting shorter (we’re talking two to three weeks), manufacturing and release of pDNA and mRNA are still rather long (two to three months, depending on the need for cell banks).

There is a growing interest in cell-free DNA templates, modified nucleotides, and mutant T7 polymerases and a focus on simplifying the unit operations involved in production.

LNPs, while perhaps a less complex manufacturing process on paper, are completely different products than mRNA. Shear sensitive and unstable, the processes require tight controls for consistent results. The LNP composition, formulation stability, and delivery (intramuscular, sublingual, nasal, point of care) continue to present new opportunities and drawbacks.

On the clinical side, mRNA is taking off in the personalized medicine space, drastically changing the expected scale and speed at which these products are made and altering the strategy of how and when a company partners for GMP production.

Tech transferring a process too early can get you stuck in a process with little room for improvements or lead to an overwhelming number of comparability studies down the line.

In contrast, when the expectations for manufacturing are in flux and knowing that tech transfer may cause headaches, developers might even ask: “Do we really need a CDMO yet?”

It can be tempting to delay tech transfer to a CDMO as long as possible; hence, tech transfers happen too late. If nothing else, preparing for GMP production then actually manufacturing a product creates more work and documentation. Eventually, a successful product is going to need a CDMO, or at least a dedicated manufacturing team. “Good” CDMOs have resources and expertise. They know the scope of GMP manufacturing through Phase 1 to Phase 3. If they also have flexibility to navigate uncertainty, partnering will almost certainly streamline future production and reduce process changes between phases.

Juggling the timing of the partnership with ongoing process development should be a key part of any leadership’s strategy when considering getting into a GMP-certified cleanroom.

Diversity Within The “Platform”

RNA is typically considered a nimble “platform technology” – a drug substance and a drug product produced the same way for different indications. At a high level, this is true.

However, changes in critical raw materials may be considered platform changes. DNA templates of significantly different sizes or design features can impact the efficiency and purity of the IVT, efficiency of downstream purifications, and packaging.

Changes to the lipid composition, especially the ionizable or cationic lipid, require new in vivo translation and toxicity studies. Moreover, the RNA field has far more diversity than mRNA-LNPs. RNA technologies vary significantly between companies, and new technologies continue to emerge.

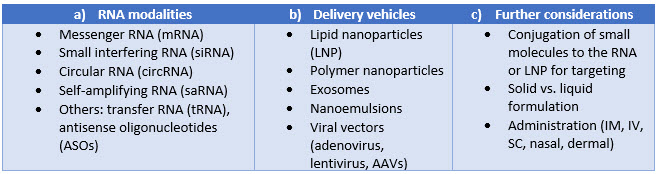

Even organizations that have mRNA-LNP pipelines are inventing new ways to improve efficiency and performance. Table 1 (below) lists several common RNAs and delivery vehicles.

The RNAs may be paired with a different delivery vehicle for a given application. Some have similar manufacturing needs; others are drastically different. The final formulation and filling will be completed based on how the therapeutic is to be administered. CDMOs will lack exact expertise in every potential combination, but they may be highly experienced in similar processes. Evaluation of CDMOs and selecting one with related technologies and expertise to the methods being transferred is likely to result in better success.

Table 1. Manufacturing segments within RNA therapeutics. Several RNA (a) and delivery technologies (b) are in exploration, along with considerations (c) that further add complexity and variability to the manufacturing process.

Conclusion

At its simplest, tech transfer is the introduction of a product and/or process to a new facility and/or team. It is often all four, but not always. Usually, tech transfer is done in preparation for GMP manufacturing and commercialization.

Given the points discussed in this article, developers and CDMOs need to start deconstructing the other assumptions of tech transfer and be flexible in all questions of “who, what, where, and when” and lay out a GMP manufacturing strategy that makes sense for their teams and products.

Overall, RNA therapeutics have incredible potential. It will be exciting to see the space grow to serve more and more patients over the next 10 years as these therapies come to fruition. From a CMC perspective, it is true there are many unknowns. Limited experience, changes in strategy, and ongoing process and product development contribute to slow progression of these therapies to highly controlled, regimented manufacturing environments.

However, knowledge of RNA is spreading. In the meantime, we will only gain more clarity on the requirements, timelines, and overall strategy for success from those companies that are currently paving the way. While the rules of the game remain unclear, developers and CDMOs alike can be flexible and creative in their approach, timing partnerships to provide exceptional products to patients everywhere.

About The Expert:

Victoria Fong is a research engineer with over six years of industry experience. She has focused on process design and optimization, specifically within the development of mRNA-LNP therapeutics. Victoria holds a BASc and MASc in chemical engineering from Queen's University and continues to explore dynamics and opportunities at the intersection of engineering and life sciences.

Victoria Fong is a research engineer with over six years of industry experience. She has focused on process design and optimization, specifically within the development of mRNA-LNP therapeutics. Victoria holds a BASc and MASc in chemical engineering from Queen's University and continues to explore dynamics and opportunities at the intersection of engineering and life sciences.