"To Thine Own [mRNA Product] Be True:" Shakespeare's Guide To RNA GMP Principles

By Anna Rose Welch, Editorial & Community Director, Advancing RNA

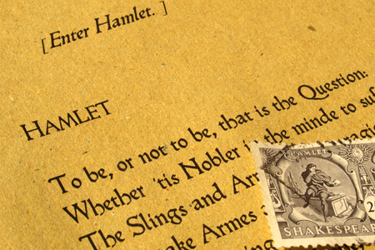

As a poet, I’m a sucker for anything that brings literature and pharma together. So, it should go without saying I felt like an overjoyed nerd in an advanced literature seminar during the Hamlet-inspired panel, “To GMP or not to GMP” at the Hanson Wade mRNA Process Development & Manufacturing Summit last fall. And frankly, I can’t think of a more befitting combination than that of GMP principles and poetry — if only because both are prone to a high degree of subjectivity. If you ask a room of experts how they define “phase appropriate” or “representative” materials, you’ll most likely get an array of different responses depending on the company, the expert’s functional area, the product itself, and the amount we know about our process and its impact on our product.

Having recently just hosted the inaugural Advancing RNA LIVE on the mRNA therapeutics supply chain, it’s clear that, despite our growing understanding of our raw materials themselves, we still remain challenged to understand the impact those materials have within our processes as a whole. This conversation becomes even less cut and dry given our current lack of regulations, our nascent understanding of RNA structure and function, and the fact that we’re working on multiple modalities and applications. (We are not a homogenous space!)

There was no better example of our space’s heterogeneity than the “Shakespearean-inspired” GMP panel at the Hanson Wade summit last fall. Together, four experts walked us through their philosophies around how they integrate GMP-compliant materials into their processes for their specific RNA therapeutic approaches (i.e., gene editing; protein replacement; in vivo CAR-Ts). They also provided several best operational practices for companies weighing partnerships with suppliers in this quickly growing space. As has been emphasized many times in the past — and as I was reminded in this recent article — improving the quality of raw materials for our products is not nor can it be a one-sided effort undertaken solely by our supplier partners; it requires ongoing transparency into and dialogue around how our — and in turn, the broader industry’s — quality needs are and will change throughout our products’ maturation.

In the following article, I offer some of the biggest tips and tricks from this GMP panel, albeit with a little bit of help and wisdom from “The Bard” himself. But don’t worry; since I’ve already pointed out that poetry is subjective, I have also translated these Shakesperean phrases into “normal talk” for us all — just so we’re all on the same page…

“What is past is prologue.”

[i.e., For long-term success, keep quality in mind from the beginning.]

The world is a stage upon which many experts have emphasized the importance of implementing “representative” materials into our processes “as early as possible.” But what does “the earlier the better” actually mean in the context of an mRNA/RNA therapeutics development program?

“No later than starting scale-up runs in a pilot plant setting,” one expert offered.

“We strive to have one or two assessments of certain GMP-compliant materials — namely enzymes and NTPs — before tech transfer prior to scale-up,” another expert shared.

“Whether it’s a scale-up run that isn’t technically an engineering run yet, or toxicology studies, or an engineering run, we try to use the same reagents — the same catalog numbers — that we use in a GMP run,” another panelist explained.

In fact, as the fourth panelist furthered, using GMP-compliant, as opposed to research-use only (RUO) materials, may prove to be exceptionally important in certain “critical” animal studies as well as for toxicology studies — particularly because RUO materials can contain residual impurities that can increase dsRNA production and/or trigger “false alarm” side effects.

Now, as you can imagine, “to GMP or not to GMP” is not necessarily always a black-and-white equation. As the panel went on to discuss, there are situations in which relying on RUO materials makes sense — for example, when optimizing manufacturing scale and yield. Likewise, as several speakers acknowledged, depending on the vendor and material, the manufacturing process for a RUO material may be the same as that of its GMP-compliant version. In such cases, the biggest difference will be the amount of documentation and/or QA oversite accompanying each material. In turn, we may find that we can justify RUO materials, so long as we’ve (stringently) done our risk assessment due diligence and have high confidence that there are no “meaningful” differences between the RUO and GMP material(s).

"The fault is not in our stars, but ourselves."

[i.e., “Don’t leave material quality to ‘fate’ — ask your partners the right questions”]

Overall, it’s important to keep in mind that, as we’re a growing space, there remains great variability between vendor supplies for some of the most critical drug product-related raw materials — particularly lipids, enzymes, and capping reagents.

“These are the main categories of materials where you will see more difference between material grades,” one speaker added. In fact, look no further than this slide from the recent USP mRNA Open Forum which nicely showcases the differences between four different suppliers’ testing of T7 polymerase.

“There’s a lot of vendor-to-vendor variation out there,” the speaker continued. “It’s not a matter of ‘if,’ it’s a matter of ‘when.’ So, addressing such variability early in your process development is critical.”

In addition to auditing a supplier’s facility, as well as carefully weighing their (ideally validated) processes and quality management systems, the members of the panel all went long on the importance of traceability and documentation for materials and components. Afterall, components and materials can and often do change over time, which can throw a loop in the most controlled processes. As one speaker emphasized, a core element of their technical quality agreements is that they (the biotech) receive notifications of any changes to an existing material or component.

Likewise, several other speakers pointed to our ongoing efforts to avoid using animal-derived products. (Please note: CBER is coming out with guidance in 2024 on considerations for human and animal-derived materials & components in CGT manufacturing…) However, as is to be expected, striving to ensure a material is animal origin-free can cause some additional lift — and perhaps stress — on behalf of the biotech to “go back to Adam,” if you will. For example, as one speaker shared, he was in a situation in which a non-drug-substance-related material with “foggy” origins (namely, the restriction enzyme for linearizing plasmid) completely derailed a company’s progress into the clinic.

‘The material was made by a verified process,” the speaker shared. “However it was not what you would consider a GMP-compliant material. The regulatory authorities asked about the origins of the material all the way back to the source of how it was made. Unfortunately, the vendor did not have that information.” Nor (at the time) was it possible to find another supplier that could supply the material with the proper documentation — at least not in a short amount of time at an affordable price. In turn, this barred the company from entering the clinic.

“I can’t stress how important it is to not treat your raw materials as commodities today,” the speaker concluded.

"Modest doubt is called the beacon of the wise."

[i.e., “Don’t take a COA at face value.”]

Just as we shouldn’t consider our materials commodities, it’s also important that we not treat our relationships with our supplier partners as transactional commodities. In these (still) foundational days as we strive to understand the complex biology of our products, there’s a lot we can learn from each other (biotechs and suppliers) as we bring our therapies and the materials underpinning them to new heights.

If there was one best practice that came through this panel loud and clear, it’s to look more deeply into the COA to better understand each raw material’s quality. In an ideal (and hopefully our future) world, we hope that our supplier partners’ material specifications and the specs that our processes/specific products demand will be closely aligned — but unfortunately, this is not always the reality today.

It may be the case that some materials require additional testing/documentation of additional CQAs within a COA. However, if there was one area all panelists were aligned, it was around the best practice of engaging in an ongoing dialogue with our partners to ensure that a material’s specs are tightened over time.

Though a material may have passed a supplier’s release specifications, “What we’ve found is that some of these ranges they’re testing against are so long you can drive a truck through them,” one speaker said. “You have to look closely and ask yourself, are these specifications —particularly those for our critical raw materials — appropriate for what we’re trying to do?”

“Not all that glitters is gold.”

[i.e., “GMP ≠ Grade”]

If “brevity is the soul of wit,” then this paragraph is going to be the wittiest you’ve ever read.

As both this panel AND a previous FDA CGT Town Hall nicely remind us: GMP is not a grade, nor is it a term denoting a material’s quality. It’s both a marketing term that will vary widely by supplier, as well as a descriptor of the environment in which a material is made.

Fin.

![“To Thine Own [mRNA Product] Be True” Shakespeare's Guide To RNA GMP Principles](https://vertassets.blob.core.windows.net/sites/logos/rna.png)