The Great Cell Therapy Reset: Solving The Industrial Math Of Living Drugs

By Johnathon Anderson, Ph.D., associate professor and program officer, University of California Davis School of Medicine.

In late 2025, the cell therapy sector appeared to hit a wall. In the span of a few weeks, industry bellwethers like Takeda, Novo Nordisk, and Galapagos announced they were unwinding or exiting their established cell therapy units. To the casual observer, this looked like a bubble bursting. But for those of us in bioprocess engineering and CMC strategy, the signal was different.

This isn’t a failure of biology; it is a correction in manufacturing strategy. The exits we are seeing represent a forced evolution away from a first-generation model that was operationally unscalable. We are witnessing the end of the ex vivo cell processing era and the birth of in vivo CAR-T.

For pharma executives, the lesson is clear: The science of CAR-T works. The logistics of Gen 1.0 are broken. The teams that solve the latter, converting bespoke services into standardized products, will inherit the market.

The Problem: The Service Vs. Product Trap

To understand why major players pulled the plug, we must look at the unit economics of first-generation autologous ex vivo CAR-T. For the last decade, the industry standard has relied on an autologous supply chain that functions less like a pharmaceutical manufacturing operation and more like a high-complexity service bureau.

The vein-to-vein workflow is fraught with operational friction: apheresis at the clinical site, cryopreservation, cold-chain logistics to a centralized GMP facility, and weeks of ex vivo transduction using expensive lentiviral or retroviral vectors. This is not drug manufacturing; it is bespoke cellular processing.

The bioavailability tax on this architecture is prohibitive. The reliance on complex logistics and cleanroom residence time drives the cost of goods sold (COGS) to unsustainable levels, crushing margins and limiting patient access. Worse, the process introduces massive batch-to-batch variability. Because every patient’s starting material is different, the final drug product is inconsistent, creating a regulatory and quality control minefield.

From a quality assurance perspective, the process is the product dogma introduces unmanageable risk. Because the starting material (patients’ T cells) suffers from high biological heterogeneity, maintaining consistent critical quality attributes (CQAs) in the final drug product is nearly impossible. This creates a regulatory minefield for potency assays and release testing, where batch failures are statistically inevitable.

While this high-touch artisanal model is viable for ultra-rare oncology indications with high reimbursement ceilings, the industrial math collapses when applied to autoimmune populations. You cannot scale a bespoke, manual manufacturing process to treat millions of patients without a fundamental change in the unit of operation.

The Solution: The CMC Pivot (From Bioreactor To Body)

The solution is not to stop engineering cells. While some have looked to allogeneic (donor) cells as a stopgap, that approach still relies on complex ex vivo processing. From a CMC perspective, the true shift is to in vivo CAR-T via lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). This shifts the paradigm from manufacturing a patient-specific service to manufacturing a standardized chemical product.

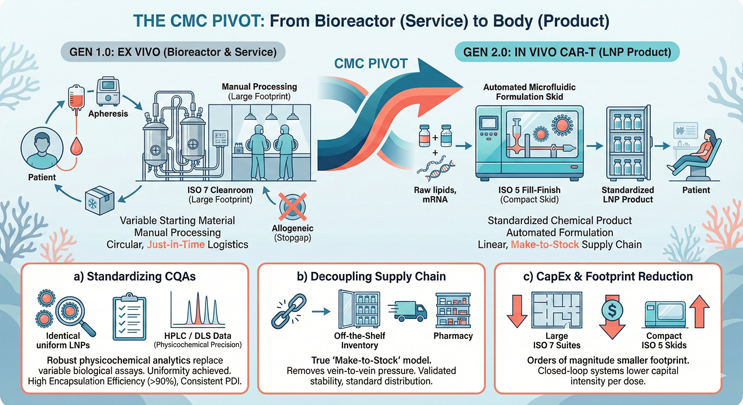

Figure 1: This split-screen infographic illustrates the CMC pivot from Gen 1.0 to Gen 2.0. The left side (Gen 1.0 Ex Vivo) depicts a circular vein-to-vein supply chain characterized by complex cleanrooms, bespoke patient scheduling, and high COGS. The right side (Gen 2.0 In Vivo) depicts a linear pharmaceutical supply chain using LNPs. Key features include standardized microfluidic formulation skids, make-to-stock inventory vials, and a simplified delivery model that moves from factory to pharmacy.

- Standardizing CQAs: In autologous therapy, high variability in patient apheresis material makes defining and maintaining CQAs a statistical challenge. With in vivo delivery, the drug product is the LNP itself, not the cell. We can characterize the lipid-to-mRNA ratio, polydispersity index (PDI), and encapsulation efficiency (>90%) with small molecule precision using standard HPLC and DLS methods. This replaces variable biological potency assays with robust physicochemical analytics, satisfying regulatory demands for uniformity.

- Decoupling the Supply Chain: The move to in vivo creates a true make-to-stock inventory model. We effectively decouple manufacturing from patient scheduling, eliminating the just-in-time pressure of vein-to-vein logistics. The therapy becomes a frozen, off-the-shelf vial with a validated stability profile, distributable through standard pharmaceutical channels.

- CapEx and Facility Footprint: We replace the need for thousands of square feet of ISO 7 (Grade B) cell-processing suites and labor-intensive open manipulations with compact, closed-loop microfluidic formulation skids. This shrinks the manufacturing footprint by orders of magnitude and allows for production in standard ISO 5 (Grade A) fill/finish environments, dramatically lowering the capital intensity per dose.

The Technology: Engineering Out Of The Liver Trap

For formulation scientists, the primary barrier to in vivo adoption has been the liver trap. Standard ionizable lipid formulations, largely optimized for hepatic delivery (e.g., transthyretin amyloidosis), rely on the adsorption of endogenous Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) in the bloodstream to facilitate uptake via low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors on hepatocytes.

While highly effective for liver targets, this passive targeting mechanism effectively sequesters >90% of the dose in the hepatic sink, rendering it useless for blood cancers or extra-hepatic immune modulation. The industry is now overcoming this biodistribution bottleneck through active receptor targeting.

The breakthrough lies in the maturation of targeted ionizable lipids (such as the L829 series) capable of stable conjugation with active targeting ligands. By chemically anchoring antibodies, specifically anti-CD8 or anti-CD5 moieties, directly to the LNP surface, we shift the uptake mechanism from passive LDLR-mediated endocytosis to active receptor-mediated endocytosis.

This surface engineering allows the LNP to actively hunt T cells in the systemic circulation, effectively bypassing first-pass hepatic clearance. The result is a dramatic shift in biodistribution: we achieve high-efficiency transfection of cytotoxic T cells at significantly lower total lipid doses, minimizing hepatotoxicity while maximizing the therapeutic index.

The Safety Dividend

While the primary driver for in vivo adoption is operational scalability, the shift to non-viral xRNA platforms offers a structural regulatory advantage. By moving away from integrating viral vectors, developers can bypass some of the most burdensome safety monitoring requirements that currently stifle the cell therapy commercial model.

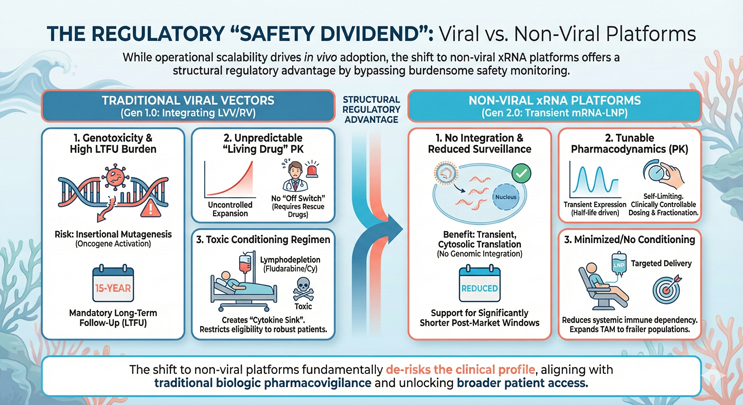

Figure 2: This infographic shows a side-by-side comparison of the safety profiles for Gen 1.0 viral vectors versus Gen 2.0 non-viral mRNA-LNPs. The left side (Viral) lists risks including insertional mutagenesis, permanent genomic integration, and mandatory 15-year Long-Term Follow-Up (LTFU). The right side (Non-Viral) highlights three key regulatory advantages: 1) zero risk of genomic integration (non-mutagenic); 2) tunable pharmacokinetics via transient expression (allowing physicians to stop dosing if toxicity occurs); and 3) reduced dependency on toxic lymphodepletion chemotherapy.

- Genotoxicity and LTFU Reduction: A primary friction point for lentiviral (LVV) and retroviral platforms is the risk of insertional mutagenesis, the random integration of the transgene into the host genome, potentially activating oncogenes. This risk necessitates a mandatory costly 15-year long-term follow-up (LTFU) period for patients. In contrast, mRNA-LNP payloads function via transient, cytosolic translation without nuclear entry or genomic integration. This distinct safety profile supports a pathway toward significantly reduced post-market surveillance windows.

- Tunable Pharmacokinetics (PK): With traditional ex vivo CAR-T, the drug is a living, proliferating agent with unpredictable expansion kinetics. Once infused, there is no off switch short of emergency rescue drugs (e.g., tocilizumab/corticosteroids) if toxicity spirals. In vivo mRNA expression offers tunable pharmacodynamics. Because the expression is transient and driven by the half-life of the mRNA, adverse events are self-limiting. Physicians can fractionate doses or halt administration entirely, reintroducing a level of clinical control analogous to traditional biologics.

- Minimizing the Conditioning Regimen: Standard CAR-T protocols require lymphodepletion (typically fludarabine/cyclophosphamide) to create a cytokine sink for the engrafted cells. This toxic preconditioning restricts eligibility to patients robust enough to tolerate chemotherapy. Highly targeted in vivo delivery reduces the dependency on systemic immune rebooting, potentially eliminating the need for lymphodepletion and expanding the total addressable market (TAM) to frailer, treatment-experienced populations.

Conclusion: The Infrastructure Play

The recent headlines regarding major pharmaceutical exits from the cell therapy space are a lagging indicator. These organizations are not rejecting the modality; they are reacting to the terminal unit economics of the Gen 1.0 operating model. They are signaling the end of the service-based era.

The future of the sector belongs to the organizations that view cell therapy not as a biological discovery challenge but as a delivery and logistics challenge. By eliminating the apheresis bottleneck and converting the therapy from a high-complexity procedure into a shelf-stable drug product, we decouple the treatment from the academic medical center. This effectively unlocks the community oncology market, transforming the TAM from thousands to millions.

For the industry, the strategic mandate is unambiguous: The era of competing on cleanroom capacity is over. The next cycle of value creation will be defined by delivery infrastructure. We must stop investing in centralized GMP processing suites and start investing in the non-viral vectors that render them obsolete.

About The Author

Johnathon Anderson, Ph.D., is an associate professor and program officer at the University of California Davis School of Medicine, where he focuses on the discovery and development of cell and gene therapies. His work bridges the divide between high-level academic research and the clinical manufacturing realities of the cell and gene therapy space. Beyond his faculty role, he serves as the deputy editor for The Journal of Extracellular Biology.

Johnathon Anderson, Ph.D., is an associate professor and program officer at the University of California Davis School of Medicine, where he focuses on the discovery and development of cell and gene therapies. His work bridges the divide between high-level academic research and the clinical manufacturing realities of the cell and gene therapy space. Beyond his faculty role, he serves as the deputy editor for The Journal of Extracellular Biology.