One Unspoken Issue With The FDA's Platform Designation

By Anna Rose Welch, Editorial & Community Director, Advancing RNA

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been sharing some of my thoughts on the FDA’s Platform Designation guidance. (You can find the previous two parts here and here.) Though the guidance has been the topic of great excitement in the RNA space, there has been an equal amount of disenchantment and/or confusion about how this designation may function differently than the seemingly familiar concept of “prior knowledge.” There has also been an equal amount of frustration over the fact that this guidance will only apply to companies that have previously approved at least one product.

Having been an industry observer for more than 10 years now, there are a few things I can say with great certainty when it comes to any regulatory guidance. One: All guidance comes with the caveat that agency recommendations are/will always be product specific and will depend heavily on the program’s totality of the evidence and the CMC reviewers. And two (which is my favorite): As an industry, we have a penchant for regulatory gossip that could easily rival the drama of a television series. (#GossipGirlPharma.)

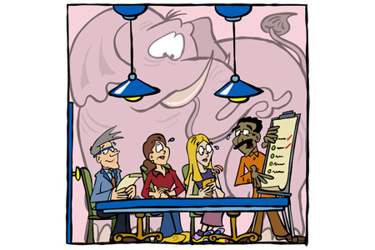

Both these certainties may be “duh-worthy” to those of us who live and breathe the regulatory world. But these two realities bring to light a challenge I anticipate we’ll continue to face as we see (or don’t see) companies garnering platform designations in the future. Subjectivity and hearsay will no doubt play a big role in how we approach this guidance moving forward, and I daresay these hard to mitigate factors will complicate our relationship with this designation in the future.

As a poet, I use the phrase “It’s all subjective” at least 10 times each day. But over the past few years living in the pharma industry, I’ve been tickled to realize that regulatory affairs and poetry (and visual art, for that matter) have some degree of subjectivity in common far more than I would’ve anticipated. We regularly hear about the current and future state of ATMP regulatory affairs from the “figure head” regulatory officials, namely the FDA’s Peter Marks. However, as we also know, his views/ideas are not always shared by our individual CMC reviewers. Look no farther than the rather controversial approval of Sarepta’s gene therapy Elevidys last year on which Marks had the final say over hesitant reviewers.

Likewise, having spent the past few years in the advanced therapies space, I’ve also been keenly aware of how easy it can be to take one company’s regulatory experiences — both positive or negative — as gospel. This has never been more apparent than during the CGT space’s squabbles with potency assays over the past few years — the resulting hearsay/myths and/or nightmares of which only served to increase the drama of the CGT regulatory experience and, frankly, left some regulators quite bewildered. (Please refer to best practice #3 for context here).

I highly anticipate we will run into similar challenges, be they spurred on by subjectivity or hearsay, in the years ahead when it comes to the platform designation. So far, the concept of the platform — particularly in the regulatory sense — has been highly subjective. At a conference earlier this year, I couldn’t help but laugh when hearing Marks admit that the agency will “know [a platform] when we see it.” We can see this current “fuzziness” reflected in the language of the guidance itself. Some of my favorite phrases included: A “reasonable likelihood of significant efficiencies (4);” “minor differences in product design, operating conditions, and/or context of use (8);” and “nearly identical manufacturing processes for drug substance/drug product…(5).”

Likewise, as I explained in this previous article on the platform designation, there’s already a breakdown in understanding “the platform” at a very basic vocabulary level. While those of us in the industry may think of the platform solely in the terms of CMC/manufacturing technology, other non-FDA regulators prefer the phrase “prior knowledge” (as opposed to “platform”) to describe the act of carrying over data/experiments/elements across products.

Now, to be clear, the agency is seemingly aware of the subjectivity plaguing the general “amorphous” nature of the platform. In fact, recent conversations I’ve heard have indicated that this guidance was, in large part, a first attempt at breaking the lofty, hard-to-define-concept of a platform into more consistent and measurable elements — or “building blocks,” as the Alliance for Regenerative Medicines coined it. Though prior knowledge may be a more consistently defined concept in the industry compared to “platform,” we ultimately can’t ignore the fact that leveraging prior knowledge in a regulatory application is still very much an art. And just as every artist has their own style/approach to their subject matter, so too, do regulators when assessing prior knowledge (and risk) in a product’s regulatory filing.

As a speaker at a recent conference emphasized, this draft platform guidance at least promises to formalize and eliminate inconsistencies in regulatory assessments of such building blocks. Whether the final guidance will live up to this promise, however, remains to be seen; and, unfortunately, for those of us in the mRNA therapeutics space, it’s likely we will be waiting a long time (and be confronted with lots of hearsay in the meantime) before we get our answers.